ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31408

CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE EDUCATION: EDUCATIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE THIRD SPACE

La educación culturalmente receptiva: análisis educativo del tercer espacio

Ángel LLORENTE VILLASANTE, Martha Lucía OROZCO GÓMEZ and María SANZ LEAL

Universidad de Burgos. España.

alvillasante@ubu.es; mlorozco@ubu.es; msleal@ubu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8540-974X; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5547-8712; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9845-0688

Date of receipt: 04/04/2023

Date accepted: 02/08/2023

Date of online publication: 01/01/2024

ABSTRACT

In the face of increasingly polarized societies, there is evidence to show that hate speech towards diversity is proliferating at alarming rates, provoking intense social disparities. It can often influence the social inclusion of young people from multiple cultural backgrounds, in so far as assimilation is presented as the first option without adopting a critical perspective. The education system must in that sense take steps to address cultural diversity within the classroom through approaches that educate students and enable meaningful learning. Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) contributes to adequate management of that diversity, relying on forms of conceptualization and development that deserve to be analyzed from within various educational and social spheres. In this study, a critical review method and discourse analysis are used to observe the development of CRE from the perspective of both teachers and students. Few studies have explored a discourse analysis of CRE through the Funds of Knowledge (FoK) approach applied to classroom pedagogy and the role of the teacher, and the Funds of Identity (FoI) approach applied to the students. Thus, the aim here is to analyze the pedagogical dimension of the teacher within the classroom through the FoK approach, while the student perspective is contemplated through the FoI approach. Through this analysis, an educational reinterpretation of the Third Space is suggested, making a contribution to CRE and its work within the classroom. Finally, we outline some challenges of CRE with regard to its terminology, implementation, and future lines of work.

Keywords: culturally responsive education; funds of knowledge; funds of identity; cultural diversity; third space.

RESUMEN

Ante sociedades cada vez más polarizadas, la evidencia muestra cómo los discursos de odio hacia lo diferente proliferan alarmantemente provocando mayores disparidades sociales. Esto influye frecuentemente en la inclusión social de jóvenes con influencias culturales diversas presentando la asimilación como primera opción sin adoptar una perspectiva crítica. El sistema educativo debe actuar en este sentido abordando la diversidad cultural en las aulas desde enfoques que permitan la formación del alumnado y posibiliten un aprendizaje significativo. La educación culturalmente receptiva (ECR) contribuye a una adecuada gestión de esa diversidad contando con variantes respecto a su conceptualización y desarrollo que merecen ser analizadas desde diferentes esferas educativas y sociales. En este artículo se utiliza un método de revisión crítica y análisis del discurso para observar la evolución de la ECR desde la figura del profesorado y alumnado. Pocos estudios han explorado el análisis del discurso de la ECR desde metodologías de fondos de conocimiento (FdC) con pedagogías dentro del aula en el papel del profesorado y fondos de identidad (FdI) del estudiantado. Por ello, este estudio tiene como objetivo analizar la dimensión pedagógica del profesorado dentro del aula desde FdC y desde la figura de los y las estudiantes y su aprendizaje se contemplan FdI. Desde este análisis se sugiere una reinterpretación educativa del tercer espacio que permite una contribución para el trabajo de la ECR en el aula. Por último, se señalan algunos desafíos de la ECR respecto a su terminología, implantación y futuras líneas de trabajo.

Palabras clave: educación culturalmente receptiva; fondos de conocimiento; fondos de identidad; diversidad cultural; tercer espacio.

1. INTRODUCTION

Throughout history, social groups have been culturally engaging with their peers and, as Harari noted (2014), ever since their emergence, embryonic cultures have continued to change and to develop. At times, these cultural changes and development have been and are questioned, with widespread social demands for uniformity and sameness (Han, 2017), unaware that there can be no self without the other. Intercultural relationships between groups are therefore often debated in certain social sectors that attempt to replace them with uniformity, forgetting that diversity helps shape us as individuals. In the modern world, changing and in a constant state of flux (Bauman, 2017), understanding the increasingly complex cultural realities of students is a delicate task. These realities are characterized by superdiversity (Vertovec, 2007) that can be difficult to address, both for society, in general, and for the educational environment, in particular. The situation calls for cross-disciplinary teacher training that is responsive to cultural diversity. The potential achievements of some if not many students are often diminished, due to the reductionism of educational systems that limit critical consciousness and cultural capital, as noted by Bourdieu (1986), provoking further inequality in society. It is essential to see each student as a source of development and cultural wealth, to achieve emancipatory teaching that educates the learners and that generates intrinsic value through mutual support (Garcés, 2020).

Spanish educational policies designed for linguistic-cultural management are focused on linguistic aspects with measures aimed at the vehicular language (Olmos-Alcaraz, 2016), but such policies overlook cultural aspects that also require attention. Certain studies (Bayona et al., 2020; OECD, 2018; Schleicher, 2019) have shown that basic levels of academic competence are less likely to be achieved among students whose cultural backgrounds are diverse than among their native Spanish counterparts. Those same students are also less likely to feel a sense of commitment to an educational institution in which their families are also less involved and to which they are less well socially adapted. Initiatives such as compensatory education in no way solve underlying social difficulties (González Faraco et al., 2020) that can lead to the assimilation of identities that adopt opposing stances.

Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) addresses these assimilation processes, seek in to prevent their evolution into “murderous identities” (Maalouf, 2010), and weighing up cultural identity with tolerance in mind. This pedagogy originated in the United States in the 1990s and has evolved through theoretical and practical contributions that shape its meaning. The country’s characteristic migration flows highlight the need for such pedagogies, considering intrinsic social diversity and reflecting on interrelated economic, demographic, and social factors. The educational sphere should incorporate cultural references and socio-psychological aspects stemming from these migration processes. Analyzing this pedagogy has positive implications within the Spanish context, because it leads to a reorientation of the school curriculum through dialogue rooted in ethnic and cultural studies that advances teacher training within this area, and that helps to combat misconceptions regarding minority or culturally diverse student groups (Rodríguez-Izquierdo and González Faraco, 2020; Sleeter, 2018). Understanding those students within our context as students from migratory backgrounds, with no links to a predominant social group, living with relevant ethnic, linguistic, religious, and social differences, and facing greater difficulty at gaining recognization within educational practice.

In the extensive research on this pedagogical approach, discourse analysis that applies the Funds of Knowledge (FoK) pedagogical approach to the teacher’s role and the Funds of Identity (FoI) approach for students in educational practice is limited to very few studies. Consequently, the antecedents and the evolution of CRE are presented in this study, together with an analysis, based on two theories related to the main theme, suggesting an educational reinterpretation of the “Third Space” that projects new initiatives when working with CRE.

2. THE BACKGROUND TO CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE EDUCATION

Ethnic, racial, and social diversity within the United States multiplied in the classroom following the annulment of the so-called ‘Jim Crow’ Laws and the rise of the Civil Rights movement. From that point onward, various legislative acts seemingly indicated governmental commitment to educational social justice. However, those reforms associated with political and social traditionalism posed obstacles to more effective education for students from diverse cultural backgrounds (Gay, 2018).

In a context of political inaction, during the 1950s and 1960s, research advocating the adaption of educational systems to those social needs emerged, giving rise to the term “culturally responsive” (Cazden and Leggett, 1976), which served as the basis for the development of CRE (Gay, 2000). Other works, such as Ramirez and Castañeda’s (1974) on the assimilationist role of schools, not only aimed to adapt educational systems, but also questioned them, forming one of the early foundations of culturally relevant education (Ladson-Billings, 1995). There are terminological differences that lead to extensive discussions on this pedagogy (Gay, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Nieto and Bode, 2018; Villegas and Lucas, 2002), but all contributions seek a structural educational change from a critical perspective grounded in social justice, aiming for meaningful relationships between teachers, students, and families while valuing diversity (Nieto and Bode, 2018).

This pedagogy is focused on the teacher dimension and teacher training (Gay, 1978; Ladson-Billings, 1995), as well as ethnic diversity within the classroom for learning (Gay, 1994; Ladson-Billings, 1992). Initially, more attention was focused on curricular structures and adjustment (Gay, 1975; Villegas and Lucas, 2002), with a shift towards teachers as potential agents of educational change (Delpit, 2006; Gay, 2018; Villegas and Lucas, 2002). Ladson-Billings (1995) analyzed both students and teachers as transformative vectors to combat spheres of social power and authority that are present in education. Gay (2000) suggested a dialogic relationship between classroom pedagogies and both teacher and student identities to achieve this change. Both approaches were used interchangeably in the literature, and both authors, while acknowledging variations, pointed out that referring to this pedagogy with one expression or another is a matter of choice, with other contributions incorporating them into the same framework (Aronson and Laughter, 2016; Brown-Jeffy and Cooper, 2011). However, there are certain differences that can be explored through FoK and FoI.

3. FUNDS OF KNOWLEDGE AND FUNDS OF IDENTITY AS ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORKS FOR CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE EDUCATION

3.1. Funds of Knowledge and Culturally Responsive Education (CRE)

There is a clear relationship between cognition, culture, and understanding, as Nieto and Bode (2018) recently demonstrated, in so far as students feel more validated and prepared for learning when the pedagogical environment provides a culturally responsive educational response.

That cultural response is evidence of the necessary connection between family and school, beyond the one established by behavioral issues or academic performance, which is often associated with the cultural deficit perspective in education (Valencia, 2010). Cultural deficit can be counteracted in the learner through a shift in focus towards school contexts (Poveda, 2001), aiming to adapt those learning environments with meaningful family-school relationships. CRE seeks those meaningful relationships for learning, but knowledge of family realities is necessary. In that regard, Vélez-Ibáñez and Greenberg (1992) linked family cultural resources to education through ethnological research that helped teachers to gain a better understanding of academic performance. The concept, known as “Funds of Knowledge” (FoK), emerged in the U.S. in the 1990s from those anthropological studies. FoK are “historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household functioning and well-being” (Moll et al., 1992, p. 133). They aim to foster the family-school relationship and enable the enculturation of new generations. While FoK programs are not necessarily identified as CRE, they act as precursors, guiding ethnic identity and facilitating cultural relationships without prejudice or racism (Gay, 2018). Moreover, there are other studies (Zhang-Yu et al., 2023) that explore how the workings of FoK along with CRE, especially through the model of Paris and Alim (2017), are necessary to maintain the cultural heritage of students and their identities, countering hegemonic and ethnocentric discourse within the educational context. These FoK have been explored in greater depth in terms of family and academic performance (Esteban-Guitart and Saubich, 2013; Moje et al., 2011) rather than from the overall teacher perspective, although there is some research in early childhood education (Hedges, 2012).

It is a circumstance that leads us to analyze Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) through the lens of the FoK approach that teachers implement, utilizing pedagogies stemming from an inductive analysis at two levels: pedagogies within and pedagogies outside the classroom (Rodríguez, 2013). In this case, we will focus on the pedagogical review within the classroom, since the study’s emphasis is within this domain, before proposing a working proposal. These classroom-based pedagogies can be listed as three vectors:

A) Involving students in co-constructing knowledge to deepen or to expand academic understanding through FoK.

B) Recognizing and promoting the use of multiple FoK in the classroom among students, including home/family FoK, as well as FoK from youth and popular culture.

C) Moving beyond merely connecting student/family/community FoK with academic content and instruction, towards a transformative classroom process involving the reorientation of teachers and students as learners and agents within and beyond the classroom (Rodríguez, 2013, p. 95).

Vector “A” entails the pedagogical perspective of relevance in cultural and social contexts, giving voice to the experiences of both students and teachers for educational purposes. Pedagogy that opposes school hegemonies emerges from Vector “B”, particularly the cultural deficit perspective, and teacher-student interactions that promote a sense of humanity and that can reframe the curriculum. Vector “C” results in pedagogy as micro-macro awareness for personal, institutional, and social transformation.

3.2. Funds of Identity (FoI) and Culturally Responsive Education (CRE)

In the learning process, there are various domains of identity to consider beyond ethnic origins. FoK recognize student identities from family contexts, but there are other social influences that also shape their identity. FoI complement the FoK approach, considering the concerns of students and other influences beyond familial ones. These ideas are also observed in some works on CRE, which emphasize not only the relevance of cultural heritage and knowledge and their maintenance over time, but also being able to incorporate other contemporary influences (Paris, 2012).

In our context, there are studies such as the one by Zhang-Yu et al. (2021), in which it was demonstrated that working with FoI enabled students to reflect on their own culture as something real and personal, in addition to evident family influences. We therefore propose to analyze CRE through different types of FoI, and to observe how they are integrated into student learning in each study.

Esteban-Guitart and Saubich (2013) defined FoI as “those artifacts, technologies, or resources, historically accumulated, culturally developed, and socially distributed and transmitted, essential for individuals’ self-definition, self-expression, and self-understanding” (p. 201), and they differentiated between:

Geographical Funds of Identity (G.FoI.): recognition in a physical space such as a town, city, or nature reserve.

Social Funds of Identity (S.FoI): involving any person or social bond considered significant for shaping individual identity.

Cultural Funds of Identity (C.FoI): cultural artifacts (flag, emblem) used for self-identification.

Identity Practices (I.P.): activities or hobbies that are practiced and that are considered important.

Institutional Funds of Identity (I.FoI): spaces that serve to understand the world and shape behavior in it, such as school.

4. METHODOLOGY

From the methodological perspective of a critical literature review (Grant and Booth, 2009), notable elements within the field of study were identified in this research. It is narrative, chronological, and critical, offering a contribution to the work of CRE after analyzing the discourses.

The search strategy that was followed must also be presented to avoid any possible bias (Guirao Goris, 2015).

1. Identification of academic works on CRE in three databases: Scopus, WoS (Web of Science), and Dialnet during September and October 2022 (Table 1). The descriptors used were “culturally* responsive* education*” and “culturally* relevant* education*” and their corresponding terms in Spanish. Since the first descriptor was exclusively in English and studies often encompass both concepts, we decided to include the second descriptor as well. We employed the asterisk (*) symbol as a truncation tool to explore variables such as culturally/culture, responsive/response, relevant/relevance in documents published between 1995 and 2022. The search was restricted to the field of social sciences and education; document type, article; languages, English and Spanish; and keywords, “Education,” “Educational Research,” “Culturally Relevant/Responsive Pedagogy,” “Article,” “Teacher Education,” “Culture,” “Teaching,” “Students,” “Culturally Relevant/Responsive Education.”

TABLE 1

DOCUMENTS IDENTIFIED WITH SEARCH INDICATORS

Search descriptors |

Scopus |

Wos |

Dialnet |

“culturally* responsive* education*” |

472 |

689 |

42 |

“culturally* relevant* education*” |

540 |

580 |

39 |

Source: Authors’ own work

2. Reading and examination of abstracts and keywords of the documents, selecting those with greater theoretical contributions on the conceptualization of CRE and those of higher scientific impact.

3. Specific searches through books and other bibliographic reviews not included in these databases, but that clearly reflected the theoretical conceptualization, being one of the reasons for the chosen method.

4. Analysis of the sources gathered in the bibliographic section for their evaluation, allowing the reader to synthesize the original volume of publications related to the study topic.

Once this critical review was conducted, a discourse analysis was performed, focusing on the main conceptual definitions of CRE that were collected. The postmodern social categories, identity, and culture are closely related to the discourse, with the notion of discourse being valued as a fundamental category (Santander, 2011).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Analysis of culturally responsive education

Table 2 lists the most widely used definitions and significant CRE approaches, together with their respective authors, and FoK approaches towards classroom pedagogies, focusing on the role of teachers and the various types of FoI, all of which are abbreviated in Table 2 below, as explained in Section 3. The categorization is built upon a critical discourse analysis that Santander (2011) outlined, utilizing the sentence as a semantic unit of analysis, as indicated in the methodology section. The theme of the study is closely linked to cultural aspects that possess a dynamic nature and that are governed by variations and influences. Therefore, the review of concepts within cultural spheres should be ongoing, without implying incorrect starting points.

TABLE 2

ANALYSIS OF THE CRE FROM FOK AND FOI

|

Definition |

FoK |

FoI |

“A next step for positing effective pedagogical practice is a theoretical model that not only addresses student achievement but also helps students to accept and affirm their cultural identity while developing critical perspectives that challenge inequities that schools (and other institutions) perpetuate.” (p. 469). |

• Vector A • Vector C |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. I.F.I. |

|

“Using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them” (p. 29). |

• Vector A |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. |

|

“The validation and affirmation of the home (indigenous) culture and home language for the purposes of building and bridging the student to success in the culture of academia and mainstream society” (p. 23). |

• Vector A • Vector C |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. I.F.I. |

|

“It seeks to perpetuate and foster – to sustain- linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (p. 95). |

• Vector A • Vector B • Vector C |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. I.P. I.F.I. |

|

“An educator’s ability to recognize students’ cultural displays of learning and meaning making and respond positively and constructively with teaching moves that use cultural knowledge as a scaffold to connect what the student knows to new concepts and content in order to promote effective information processing. All the while, the educator understands the importance of being in a relationship and having a social-emotional connection to the student in order to create a safe space for learning” (p. 28). |

• Vector A • Vector B |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. I.P. |

|

“A mental model that is useful for identifying themes and tools of practice for closing opportunity gaps, providing a conceptual context for policies and practices that focus on Equity without marginalizing some students relative to others. It actively enlists the awareness of culture, race, ethnicity, gender, ability, and other social identity markers that shape the perceptions of educational opportunities in the interest and effort to provide meaningful learning experiences for all students” (p. 34). |

• Vector A • Vector B • Vector C |

G.F.I. S.F.I. C.F.I. I.P. I.F.I. |

Source: Authors’ own compilation

Culturally relevant education takes assertive and critical stances, looking at significant cultural symbols for students, democratizing ideas, and questioning established frameworks. Although valuing cultural and family identities of students, youth FoK within classroom pedagogies are not clearly addressed in the terminological definition, which exclude vector B. With regard to FoI, both cultural and family values, and the relationship between social inequalities and the institutions responsible for their perpetuation imply the consideration of all FoI, except for identity practices. In 2009, in her book “Dreamkeepers”, Ladson-Billings analyzed the work of 8 teachers studied 17 years earlier. The pedagogy evolved attaching greater importance to youth influences, something which impacted on the education of students across practically all spheres of identity. The teaching staff, chosen for their ideals of social justice, triggered a generational shift among some of their students, demonstrating the importance of educating for social justice and equality.

Gay (2000) sought to achieve more culturally responsive and adaptable education between family and school. However, the initial definition specified neither identity practices nor institutional identity funds, excluding vectors B and C within the classroom pedagogies of FoK. This point was addressed in the definition proposed in the third edition of her book (Gay, 2018) where this transformative pedagogy confronts the hegemonic culture of the curriculum, armed with social awareness, intellectual critique, and personal and political efficacy. Her idea evolved from secondary education to all educational spheres, broadening the initial focus on the African American population to a more open viewpoint, even reaching non-educational domains.

Hollie (2011) evaluated the cultural identities of students, including aspects such as language, gender, and social class, rather than solely focusing on racial identity, unlike other authors. The significance of language as a determinant of culture and identity was highlighted, because according to the author, it often goes unnoticed or is afforded less importance than values, beliefs, or cultural norms, yet language shapes our essence and is therefore an essential part of each culture. FoK in vectors A and B, promoting transformative learning within the classroom, is considered in the terminological reference. Yet, student youth culture in terms of identity practices is not distinctly considered in FoI, thereby excluding vector B of FoK. In the second version of her book, he outlined four pillars for practicing CRE: validation, affirmation, construction, and bridge-building. His approach aims to validate and to affirm students’ culture and language, enabling the building of relationships with them to develop necessary academic and social skills, with greater attention on student youth culture through identity practices.

Culturally sustainable education seeks out the cultural relevance of the students, maintaining and valuing cultures that are frequently marginalized. Its incorporation into this analysis is important, because it originates from Ladson-Billings’ (1995) work, representing a necessary step forward built upon her previous ideas (Ladson-Billings, 2014). It aims to challenge Western dominance, achieving the decentralization of cultural hegemony (Paris and Alim, 2017), and utilizes education to invigorate communal ways of life and to analyze sovereignty and colonial relationships that influence social and educational rights. This form of education is not aligned with current educational systems, as it either transforms the school or returns it to previous contexts where community and culture are changing, yet always present, thereby asserting the definition that includes FoK in classroom pedagogies across all three vectors. Similarly, all FoI are considered, leaving students open to both contemporary and traditional influences.

Hammond (2015) analyzed how cognitive processes improved through cultural treatment, leading to independent learning in each student. She recognized Culturally Responsive Education (CRE) in mental and psychological terms, an aspect often overlooked in educational spheres. According to the author, epistemologically, the term is composed of both cognitive and cultural aspects. While certain teachers from multicultural perspectives attend to the cultural aspects surrounding the curriculum, fostering self-esteem through language or cultural identity, they neglect the cognitive area of learning and its potential where cultural heritage (Hammond, 2015) and FoI are fundamental. In her definition, the community is valued in this neuro-educational view of CRE and FoK are considered in classroom pedagogies through vectors A and B. Nonetheless, there is no explicit questioning of the social structures of inequality that promote either selective or negligent cultural attention which means that vector C of FoK is excluded, because although it is focused on personal and social transformation, the institutional aspect is not clearly observed. Likewise, the institutional FoI of the student body is excluded, as no spaces are considered to shape student behavior and to understand the surrounding world.

Drawing from influential authors, Stembridge (2020) analyzed equity within the pedagogical framework of CRE. Defining the term as a mental model, he referred to decision-making and thought processing with a sense of purpose as necessary for CRE, rather than a list of educational actions to achieve equity. A list that could never imply that intention to reflect on teaching practice, equity values, or a capability for self-renewal. He established six essential themes that constitute CRE and five key questions for its educational programming. The sensitivity or responsiveness component was given considerable attention It encompasses student-centered interests, needs, characteristics, and feelings applied to teaching that enhance learning. Hence, in his definition, FoK are considered through classroom pedagogies across all three vectors and all FoI within the students. Breaking down the term for analysis, as the author did, meant that its meaning could be reoriented. Along those lines, Cuauhtin et al. (2019) proposed Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) in a semi-algebraic manner, understanding the “C” as cultural or critical, the “R” as relevant or responsive, and the “P” as pedagogy or pluralistic, among other variations for each letter, to underpin certain ethnic studies and as a critique of other shallower forms of CRE.

5.2. Towards an educational reinterpretation of the Third Space

Following the previous analysis, we can observe the way in which FoK are considered in the various definitions, and the role of the teaching staff when implementing that pedagogical approach in the classroom. The same may be said of FoI in relation to the students. In that regard, the following paragraphs contribute to the work of Culturally Responsive Education (CRE), incorporating FoK and FoI in the classroom, and draw upon the theories of the Third Space and the vision of Cultural Ecology.

The Third Space reintroduces the value of “betweenness” in relation to both physical and ideological discourses and concepts where opposing cultural beliefs are interacting. Identities are understood to be both flexible and hybrid (Bhabha, 1994). Soja (1996) saw it as a point of intersection between place and mind where understanding confronts skepticism, enabling new alternatives. These authors perceive the Third Space as open to new interpretations, and there are works that have observed its potential in the educational field (Gutiérrez, 2008; Moje et al. 2011). Gutiérrez (2008) presented an idea of the Third Space where a shared and dialogued context is constructed between teachers and students, free from rules, where the ideas of both are legitimate and not stigmatized. Regarding ECR, Jacobs et al. (2020) illustrated the need to promote the development of third spaces for better teacher training in cultural diversity and thus CRE, including teachers’ knowledge and experiences that lead to reflection. Adapting this space to educational environments gives an understanding of otherness through a constructivist approach to the concept of the self, dialogically expanding horizontal knowledge, connecting communities, and learning from less hierarchical perspectives (Bajitín, 2000; Gutiérrez, 2008; Matusov et al., 2016). This exchange implies a peer-to-peer relationship for learning, with the teacher as a guide, as Vygotsky pointed out (1978), where the collective third space (Gutiérrez, 2008) holds significant importance. It becomes a space for the socio-historical influences of students to converge, especially those with diverse cultural experiences, including external classroom knowledge, motivations, and practices that lead to meaningful learning. As a result, these young individuals become historical actors (Gutiérrez et al., 2019) capable of projecting more positive academic futures. A neutral area of shared understanding is accessed, as Lalueza et al. (2019) showed, where FoK and FoI are included, and through dialogue different discourses emerge.

In setting up such spaces, it is interesting to consider cultural ecological theory that is used to reflect upon students from ethnic or cultural minorities, their inner relations, and their social and academic performance (Ogbu and Simons, 1998). John Ogbu distinguished between voluntary and involuntary minorities, as a way of understanding integration processes within responsive societies, differentiating between primary and secondary cultures on the basis of that concept. In this case, we will focus on its application within the education system. Ogbu and Simons (1998) pointed out that minority students receive different treatment, resulting in a different interpretation of school compared to their native counterparts. An interpretation that can, in brief, take four forms: the comparison or double frame of reference interpretation (comparison with others at school), instrumental value interpretation (such as the importance of academic achievements), relational interpretation (the degree of trust in school), and symbolic interpretation (whether the curriculum and language harm the cultural heritage of minorities). Discriminatory relational aspects, such as assimilation or subordination, and symbolic aspects, in the form of stereotypes or reductionism, as proposed by this theory, still exist in educational environments, especially within the hidden curriculum. Teachers should avoid repressive environments that hinder each student’s development, providing educational spaces for growth and shared knowledge and approaches. It will create equitable grounds upon which to question entrenched power relationships that are generated in the habitual interactions between school and community, with an exchange of identities, knowledge, and experiences through discursive hybridization (Cummins, 2001).

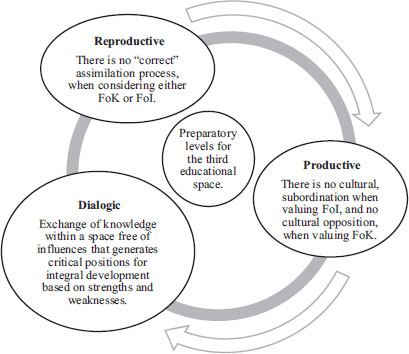

Bringing together the perspectives of both theories, we suggest three levels of student-centered work within the educational Third Space (Figure 1), aiming to reverse these interpretations with a critical attitude that strengthens and revitalizes what one knows, possesses, and feels, thereby enabling self-awareness that acts as a catalyst for personal and social growth. In its development, we also draw upon both the FoK and the FoI approaches.

FIGURE 1

PREPARATORY LEVELS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THIRD EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Source: Authors’ own work

1. Reproductive Level, identified through peer observation. Applying Ogbu and Simons’ theory (1998), this level would fit within the double frame of reference, with the difference that it occurs in an egalitarian space without having to depart from cultural or hegemonic control. There is no behavioral reference that one has to assimilate, considering and valuing FoK and FoI, which is achievable when differences are acknowledged between peers, within a free space.

2. Productive Level, recognized through peer observation and personal inquiry. In Ogbu and Simons’ theory (1998), this level was positioned between relational and symbolic adaptation, but without the need for such adaptation. First, there is individual validation and self-knowledge that can be developed through FoI, because there are no maneuvers of subordination or cultural accommodation. There is also no opposition to the cultural or linguistic framework of reference, but rather a certain selective assimilation (Portes and Rivas, 2011) in a neutral space where FoK gain value. It could be worked upon through the recognition of common and diverse aspects based on the ideas of the first reproductive level.

3. Dialogical Level, originating in dialogue with peers and self-awareness. Working on the previous levels allows for a dialogue between peers that enables the exchange of knowledge and the observation of strengths and weaknesses, creating a self-concept from both FoK and FoI. Classroom interactions, in constant change, are aligned with the ongoing interactions that constitute culture. It originates from personal ideas and feelings of empowerment and critical stances towards power relations or resources that are considered counterproductive for full personal development that may have been observed at the previous two levels.

This proposal will allow for the discovery of strengths, weaknesses, ideas, and knowledge because, as Stembridge (2020) pointed out, “the fluid nature of the classroom is one of the most sophisticated social spaces known to humans” (p. 108). Far from limiting the identity dimension for pedagogical advantage, strategies tailored to each student’s situation should be mixed, allowing for an understanding of their identity influences (Hollie, 2019; Paris and Alim, 2017; Stembridge, 2020).

Additionally, it is essential to observe spaces and processes where the exchange of FoK and FoI takes place in a transformative manner without being conditioned by ideologies or privileges (Esteban-Guitart, 2021). Some problems identified by Hogg and Volman (2020) regarding FoI can be addressed with this proposal because identity processes are not closed, but occur through interaction and constant change, reflecting necessary problematic experiences for development that also shape the identity of certain communities (Zipin, 2009), moving from hegemonic to collaborative education that also educates in adversity.

6. CHALLENGES AND REFLECTIONS

There are guidelines for applying the theoretical and epistemological work of CRE in educational practice, including cultural practices of understanding that offer field experiences and awaken the critical awareness of teachers (Ashley L. White, 2022; Emdin, 2017; Hollie, 2011; Stembridge, 2020). However, limited exposure to culturally diverse environments, coupled with a wide range of concepts and terminologies, generates confusion when implementing this pedagogy, due to a lack of knowledge and confidence (Neri et al., 2019). Teachers are the driving force for practicing this CRE with their students, giving it practical significance. Clarification regarding its evolving meaning is needed for research to continue, avoiding its trivialization, due to improper or insubstantial use (Hollie, 2019; Ladson-Billings and Dixon, 2021).

Nonetheless, it is also essential to stimulate teachers’ reflections upon their own attitudes and beliefs (Whitaker and Valterra, 2018), so that educational and cultural hegemonies are questioned without homogeneous categorizations of ethnic influences, which is an area for future studies.

Through the identification of specific and supposedly significant cultural variables, CRE contributes to building independent learning and a rigorous framework around cultural awareness, learning relationships, and information processing, fostering suitable learning environments (Hammond, 2018). As a result, the educational reinterpretation of the proposed third space is suggestive for simultaneously developing these three aspects among students, as some references to that theoretical question acknowledge that the learning styles of each student may or may not be connected to their cultural backgrounds (Paris and Alim, 2017; Sleeter, 2012). Embracing culture from folkloric perspectives is insufficient, while disregarding students’ memory, their FoK, or their FoI, which can also be influenced by jargon and violence.

Another challenge observed is its adaptability to Universal Design for Learning (UDL), with one of its methodological lines aiming to minimize cultural barriers. To do so, trivial practices in cultural diversity must be avoided, because there is currently no common learning for any one generic group. Some authors established this relationship (Kieran and Anderson, 2019; Stembridge, 2020). Marginalized CRE due to curricular design (Gay, 2018; Sleeter, 2012) might therefore find a more recognized implementation outlet in this collaborative effort, considering common causes in racism or bias against people with disabilities. Learning programs for culturally diverse students should be planned from previous didactic spaces rather than mere curricular adaptations. Working from the proposed educational reinterpretation of the Third Space could afford access to a framework that promotes meaningful learning without resorting to such adaptations. In addition to academic goals, cultural awareness, or the reduction of social disparities, CRE seeks to achieve emotional control that is not exclusively achieved through adaptations. The need for mental and emotional well-being could be significantly improved by implementing CRE in the classroom. However, it must be done with caution, because there is a risk of stigmatizing cultural practices understood as deficits within school and society, as emotions are not managed under the same norms of Western culture (Gorski, 2010).

Multicultural trends seek to manage the diversity of the “others” in the host society. CRE uses this diversity to promote the inclusion of newcomers while simultaneously enhancing self-awareness, acquiring greater social and civic responsibility in line with transformative education (Banks, 2017; Deardorff, 2010). In the global competence assessed by PISA in 2018, some authors (Sanz Leal et al., 2022; Ukpokodu, 2020) highlighted intercultural relations as a fundamental axis. It is something that CRE can develop through dimensions of participation, cultural identity, interaction, and comprehensive perception (Stembridge, 2020), serving as a foundational element of the competence situated in this practice (Kerkhoff and Cloud, 2020). These dimensions can be addressed in situated practice through work centered on the proposed educational reinterpretation of the third space, as global awareness and intercultural competence increasingly stem from diverse cultural heritages of students at the local level. However, CRE has received excessive attention at times, isolating global competence training (Ukpokodu, 2020), but conversely, one cannot fall into the trend of commodifying CRE by disconnecting cultures from their context. The challenge is to observe synergies, especially considering these latter two aspects.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of CRE in this research has led us to explore alternatives within the Spanish context for cultural management work in classrooms, considering both student-related social and linguistic, as well as identity-related factors. Our analysis has shown that CRE has gradually evolved into a more critical educational exercise through the incorporation of FoK and FoI from the perspectives of both the teaching staff and students. As a contribution to CRP-related work, an educational reinterpretation of the Third Space emerges, a strategy grounded in relevant and meaningful theories that helps overcome some of the challenges associated with CRE, stimulating the improvement of future teacher training that is all-too-often oriented towards working in culturally diverse contexts.

However, caution is advised in interpreting these statements, as they arise from a review of limited scope, necessitating further research in the future. Furthermore, another limitation of the study is linked to the fact that the proposed educational reinterpretation of the Third Space is not based on the analysis of educational practices that has been implemented. A future line of research would involve exploring how this proposal can be observed through the pedagogical practice of CRE.

Rethinking education for critical, democratic, and fair classroom practice involves promoting CRE, with its extensive trajectory, alongside initiatives such as educational reinterpretation of the Third Space, fostering learning that values the resources of each and every student that are necessary for development and learning.

REFERENCES

Aronson, B. & Laughter, J. (2016). The Theory and Practice of Culturally Relevant Education: A Synthesis of Research Across Content Areas. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 163–206. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315582066

Ashley L. White (2022) Reaching back to reach forward: Using culturally responsive frameworks to enhance critical action amongst educators. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 44(2), 166-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2021.2009748

Bajtín, M. M. (2000). Yo también soy:(fragmentos sobre el otro). Taurus.

Banks, J. A. (2017). Failed Citizenship and Transformative Civic Education. Educational Researcher, 46(7), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726741

Bauman, Z. (2017). La cultura en el mundo de la modernidad líquida. FCE.

Bayona-i-Carrasco, J., Domingo, A., y Menacho, T. (2020). Trayectorias migratorias y fracaso escolar de los alumnos inmigrados y descendientes de migrantes en Cataluña. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 78(1), e150. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2020.78.1.18.107

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241-258). Greenwood Press.

Brown-Jeffy, S., & Cooper, J. E. (2011). Toward a Conceptual Framework of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: An Overview of the Conceptual and Theoretical Literature. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(1), 65-84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23479642

Cazden, C. B., & Leggett, E. L. (1976). Culturally responsive education: A response to LAU Remedies II. In Department of Health, Education and Welfare (Ed.), National Conference on Research Implications of the Task Force Report of the U.S. (pp. 1-36). Office of Civil Rights.

Cuauhtin, R. T., Zavala, M., Sleeter, C., & Au, W. (2019). Rethinking ethnic studies. Rethinking Schools.

Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). California Association for Bilingual Education.

Deardorff, D. K. (2010). Understanding the challenges of assessing global citizenship. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad. Higher Education and the Quest for Global Citizenship (pp. 368-386). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876640-29

Delpit, L. (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. The New Press.

Emdin, C. (2017). For white folks who teach in the hood … and the rest of y’all too. Beacon Press.

Esteban-Guitart, M. (2021). Advancing the funds of identity theory: A critical and unfinished dialogue. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 28(2), 169-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2021.1913751

Esteban-Guitart, M., y Saubich, X. (2013). La práctica educativa desde la perspectiva de los fondos de conocimiento e identidad. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 25, 189-211. https://doi.org/10.14201/11583

Garcés, M. (2020). Escuela de aprendices. Galaxia Gutenberg.

Gay, G. (1975). Organizing and designing culturally pluralistic curriculum. Educational Leadership, 33, 176–183

Gay, G. (1978). Multicultural Preparation and Teacher Effectiveness in Desegregated Schools. Theory into Practice, 17(2), 149 156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405847809542758

Gay, G. (1994). At the Essence of Learning: Multicultural Education. Kappa Delta Pi.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, practice and research. Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching. Theory, Research, and Practice. Teachers Collage Press.

González Faraco, J. C., González Falcón, I., y Rodríguez Izquierdo, R. M. (2020). Políticas interculturales en la escuela: significados, disonancias y paradojas. Revista de educación, 387, 67-88. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2020-387-438

Gorski, P. (2010). Unlearning deficit ideology and the scornful gaze: Thoughts on authenticating the class discourse in education. Counterpoints, 402, 152-173. http://www.edchange.org/publications/deficit-ideology-scornful-gaze.pdf

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Guirao Goris, S. J. (2015). Utilidad y tipos de revisión de literatura. Ene, 9(2), 0-0. https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1988-348X2015000200002

Gutiérrez, K. D. (2008). Developing a Sociocritical literacy in the third space. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3

Gutiérrez, K. D., Becker, B. L., Espinoza, M. L., Cortes, K. L., Cortez, A., Lizárraga, J. R., Rivero, E., Villegas, K., & Yin, P. (2019). Youth as historical actors in the pro-duction of possible futures. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 26(4), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1652327

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press.

Hammond, Z. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching puts rigor at the center. Learning Professional, 39(5), 40–43.

Han, B-Ch. (2017). La expulsión de lo distinto. Herder.

Harari, Y. (2014). Sapiens. De animales a dioses. Una breve historia de la humanidad. Debate.

Hedges, H. (2012). Teachers’ funds of knowledge: a challenge to evidence-based practice. Teachers and Teaching, 18, 7-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.622548

Hogg, L., & Volman, M. (2020). A synthesis of funds of identity research: Purposes, tools, pedagogical approaches, and outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 90(6), 862-895. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320964205

Hollie, S. (2011). Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning: Classroom practices for student success. Shell Educational Publishing.

Hollie, S (2019). Branding culturally relevant teaching. Teacher Education Quarterly, 46(4), 31-52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26841575

Jacobs, J., Davis, J., & Hooser, A. (2020). Teacher candidates navigate third space to develop as culturally responsive teachers in a community-based clinical experience. Teacher Education Quarterly, 47(1), 71-96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26876432

Kerkhoff, S. N., & Cloud, M. E. (2020). Equipping teachers with globally competent practices: A mixed methods study on integrating global competence and teacher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101629

Kieran, L., & Anderson, C. (2019). Connecting Universal Design for Learning with Culturally Responsive Teaching. Education and Urban Society, 51(9), 1202–1216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124518785012

Ladson-Billings, G. (1992). Liberatory consequences of literacy: A case of culturally relevant instruction for African American students. The Journal of Negro Education, 61(3), 378-391.https://doi.org/10.2307/2295255

Ladson-Billings, G (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32 (3) 465-491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A. K. A. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

Ladson-Billings, G., & Dixson, A. (2021). Put some respect on the theory: Confronting distortions of culturally relevant pedagogy. In C. Compton-Lilly, T. Lewis Ellison, K. Perry y P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Whitewashed Critical Perspectives. (pp. 122-137). Taylor and Francis Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003087632-7

Lalueza, J. L., Zhang-Yu, C., García-Díaz, S., Camps-Orfila, S., y García-Romero, D. (2019). Los Fondos de Identidad y el tercer espacio. Una estrategia de legitimación cultural y diálogo para la escuela intercultural. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 45(1), 61-81. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052019000100061

Maalouf, A. (2010). Identidades asesinas. Alianza Editorial.

Matusov, E., Smith, M., Soslau, E., Marjanovic-Shane, A., & Von Duyke, K. (2016). Dialogic education for and from authorial agency. Dialogic Pedagogy: An International Online Journal, 4, 162-197. https://doi.org/10.5195/dpj.2016.172

Moje, E. B., Ciechanowski, K. M., Kramer, K., Ellis, L., Carrillo, R. & Collazo, T. (2011). Working toward third space in content area literacy: An examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), 38-70. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534

Neri, R. C., Lozano, M., & Gomez, L. M. (2019). (Re)framing Resistance to Culturally Relevant Education as a Multilevel Learning Problem. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 197–226. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18821120

Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2018). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. Pearson.

OECD. (2018). The Resilience of Students with Immigrant Background: Factors that Shape Well-being. OECD Reviews of Migrant Education, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en

Ogbu, J. U., & Simons, H. D. (1998). Voluntary and involuntary minorities: A cultural-ecological theory of school performance with some implications for education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 29(2), 155-188. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1998.29.2.155

Olmos Alcaraz, A. (2016). Diversidad lingüístico-cultural e interculturalismo en la escuela andaluza: un análisis de políticas educativas. RELIEVE-Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.22.2.6832

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Portes, A., & Rivas, A. (2011). The adaptation of migrant children. Future Child, 21, 219-246. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2011.0004

Poveda, D. (2001). La educación de las minorías étnicas desde el marco de las continuidades-discontinuidades familia-escuela. Gazeta de Antropología, 17, 17-31. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.7491

Ramirez, M., & Castañeda, A. (1974). Cultural democracy, biocognitive development, and education. Academic Press.

Rodríguez, G. M. (2013). Power and Agency in Education: Exploring the Pedagogical Dimensions of Funds of Knowledge. Review of Research in Education, 37(1), 87–120. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X12462686

Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M. y González-Faraco, J. C. (2020). La educación culturalmente relevante: un modelo pedagógico para los estudiantes de origen cultural diverso. Concepto, posibilidades y limitaciones. Teoría de La Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 33(1), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.22990

Santander, P. (2011). Por qué y cómo hacer Análisis de Discurso. Cinta de Moebio, (41), 207-224. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-554X2011000200

Sanz Leal, M., Orozco Gómez, M. L. y Toma, R. B. (2022). Construcción conceptual de la competencia global en educación. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34, 83-103. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.25394

Schleicher, A. (2019). Insights and interpretations. PISA 2018, 10.

Sleeter, C. (2012). Confronting the marginalization of culturally responsive pedagogy. Urban Education, 47, 562–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085911431472

Sleeter, C. (2018). La transformación del currículo en una sociedad diversa: ¿quién y cómo se decide el currículum? RELIEVE-Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.24.2.13374

Soja, E. W. (1996). Third space: Journeys to los angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Blackwell.

Stembridge, A. (2020). Culturally responsive education in the classroom: An equity framework for pedagogy. Routledge.

Ukpokodu, O. N. (2020). Marginalization of social studies teacher preparation for global competence and global perspectives pedagogy: A call for change. Journal of International Social Studies, 10(1), 3-34.

Valencia, R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking. Educational thought and practice. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203853214

Vélez-Ibáñez, C. G., & Greenberg, J.B. (1992). Formation and Transformation of funds of knowledge among U.S.-Mexican households. Antropology and Education Quarterly, 23, 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1992.23.4.05x1582v

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024-1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers: Rethinking the Curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053001003

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society. Harvard University Press.

Whitaker, M. C. & Valtierra, K. M. (2018). Enhancing preservice teachers’ motivation to teach diverse learners. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 171- 182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.004

Zhang-Yu, C., García-Díaz, S., García-Romero, D., & Lalueza, J. L. (2021). Funds of identity and self-exploration through artistic creation: addressing the voices of youth. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 28(2), 138-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2020.1760300

Zhang-Yu, C, Vendrell-Pleixats, J, Barreda Escrig, C., y Lalueza, J. L. (2023). Descentrar la mirada etnocéntrica: una experiencia basada en los fondos de conocimiento. Athenea Digital, 23(1), e3150. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.3150

Zipin, L. (2009). Dark funds of knowledge, deep funds of pedagogy: exploring boundaries between lifeworlds and schools, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural. Politics of Education, 30, 317-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300903037044